Dear Reader,

If there is one thing that I am known for, it certainly is for my somewhat counter-intuitive yet (mostly) pragmatic take on most things, from productivity, to careers, or product management.

After all, look at what I’ve advocated in the past

And if you are a subscriber to this letter, I am going to go on a limb and say that you either really appreciate or at least tolerate some of those somewhat left-field takes (otherwise that’s a very unfortunate Letter for you to read).

Well… You may be pleased to hear that today I’m going to up the ante. What I’m about to share today is probably one of my most extremely counter-intuitive yet oh so powerful takes I have held - and firmly stand by.

Celebrate mediocrity

I don’t think we do enough to celebrate and acknowledge where we are truly bad at. The terribly painful lack of talent that we have in some areas, the skills that we certainly do not possess. Those areas where we are hopeless beyond measure.

But we should. Behind that mediocrity hides extreme potential. Transformative potential, even.

Mediocrity holds with it the promise of a brighter dawn, of much better days, and complete reinvention, if we lean into it.

Here’s the kicker:

Being extremely bad at something can be the fuel to excellence.

Those who are terribly unskilled at something can rise to being one-percenters in the skill, and they are far more likely to get there than those who are average at it.

The single best example of this pattern, from having witnessed it first hand, is public speaking.

People who are average at public speaking rarely feel drawn (read, the pain) to improve it. Those who do, however, can become excellent at it. Toastmasters International, the global leadership and public speaking community, is a testament to that.

I spent over 7 years as a member of several clubs of Toastmasters throughout my 20s. While I started because I genuinely enjoyed the stage, the majority of my peers came in because of how uncomfortable they were with not being confident on stage, with running away from opportunities the stage would offer them.

Acknowledging this weakness, they decided to work on it. They put in the reps. So much so that some of the very best public speakers I have ever met actually started out very much petrified by public speaking. They were the “zero-to-hero” trajectory personified.

If you watch videos from the world championships of public speaking, you will come across contestants at the top of their game. Many of them started exactly like that: they went into Toastmasters because they were fed up of how painful public speaking was to them, and they turned their pain and failure into their single greatest competitive advantage.

In all my years in Toastmasters, I only came across three types of people

public speaking frightened them, so they decided to conquer it

they genuinely enjoyed naturally to be on stage and wanted more opportunities to

they had a strategic belief that public speaking would help their professional life, but felt far below average to take advantage of those opportunities

Those who are “average” or feel they are “alright, I guess” or just dislike public speaking, they either never take the step to visit or they never become active members. Only those who are naturally bad, naturally good, or strategic in their approach (and the latter is a rarity) ever thrived in that environment.

Why does it work? Why is failure a fuel?

I know. It doesn’t make sense. How does being bad at something actually qualify someone to become excellent at it?

And on the surface, it flies against everything we have ever been told. It goes against the romanticised view of natural talent being nurtured into excellence. And while this pattern certainly exists, it is not the only path, and, I’d argue, with no data to back it up, it probably is the minority path.

The truth is, humans are fundamentally driven into action by just two things: pain or pleasure.

You either do something because you enjoy it, or you are drawn to its reward,

OR

You do it because you want to avoid pain.

That’s it. Almost every motivation is a derivative of either. We run away from pain and towards pleasure.

And that’s ultimately the kicker: being bad at something can be extremely painful. So painful, that we sometimes decide to do something against it.

And because of how bad we are at that skill, we don’t have any natural intuition in how to do something. We start from the bottom of the barrel, from below zero. And that’s a blessing.

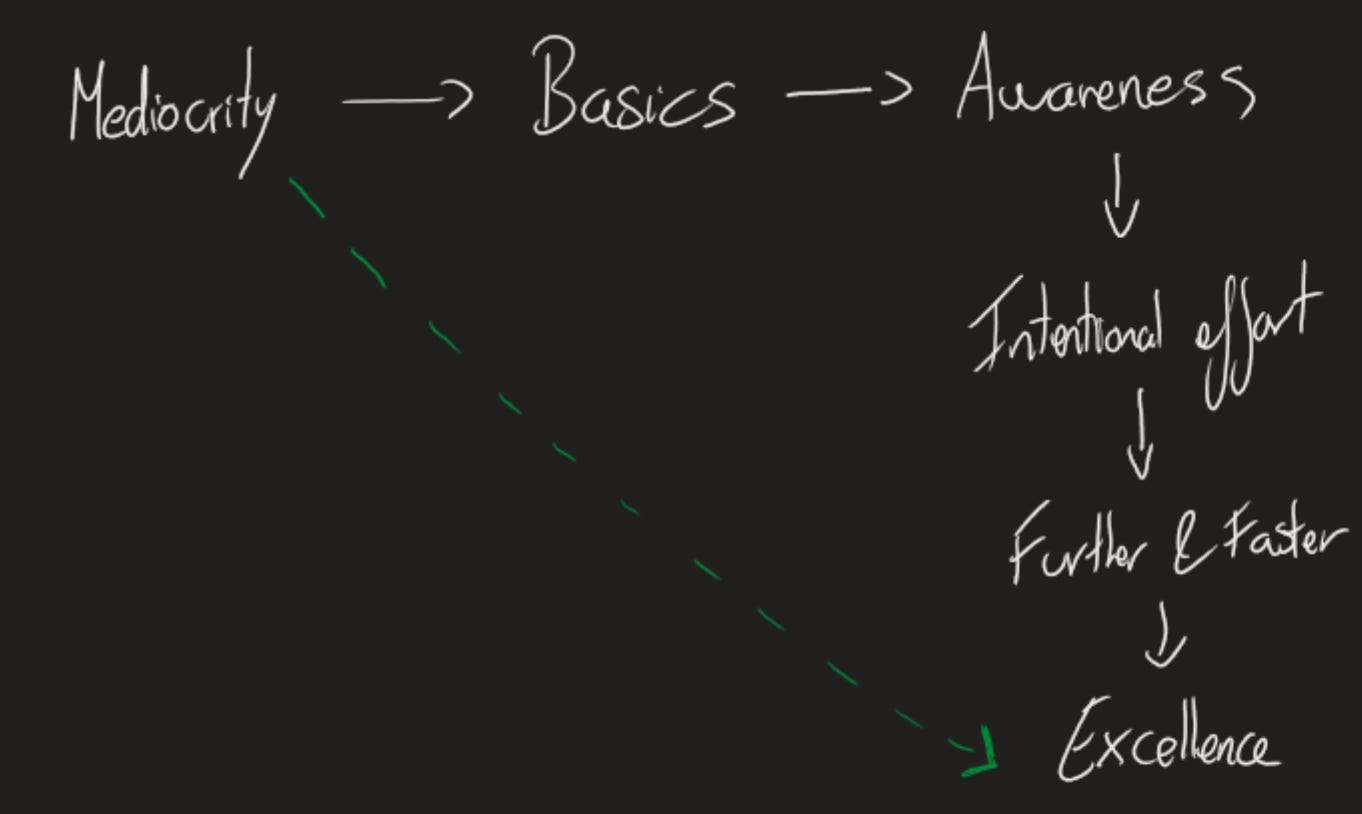

Because you don’t have an innate sense for it, you focus on understanding the basics

Because you focus on understanding the basics, you have a strong foundational understanding of this

Because you have a foundational understanding, you are also more intentionally and explicitly aware about what is good and what is bad

And because you have that explicit awareness, you shape your attention and your effort accordingly

And because this shapes your effort, you go further, farther, and faster

And this, is how pain delivers you the zero-to-hero transformation

The reality is, it’s only because their skill level was so low that they started on the journey and unlocked transformation. Had they been slightly better at it, they would not have felt the pain, and because they wouldn’t have felt the pain, they would have had very little incentive to actually get working on this.

It’s rather unscientific, but this is what it’d look like if we were to chart it:

When it comes to a big and high-value skill, being average is the worst place you can be at. It’s a lot better to be mediocre, as it will actually give you the Failure Fuel required to thrive and surpass, by a country mile, your “average” peers, and rub shoulders (and sometimes even surpass) those who are innately talented at said skill.

This is not just about public speaking

I used public speaking as the most relatable possible example, given how many people have an irrational fear of public speaking (the stat that people love to throw around in that space is that people are more afraid of death than public speaking).

But this is found everywhere. I became above average with slide and presentation design not because I have an innate sense for it (I certainly am not, my scribbles throughout this Letter would attest to that), but because of how unintuitive it all seemed to me. So I went out and studied deeply, to try and understand what rules I should follow, what mistakes most people make, and how to avoid them.

This is how I got to a level of presentation design that is much above average. I’m not claiming I am an expert - I am not, and I consciously stopped investing in the skill once I reached the level I needed to be at, but I also know that my flair for presentation design frequently puts me among strong performers, despite not having any artistic flair.

Journalist Joshua Foer is a brilliant example of that pattern in action. He always struggled with his memory, and felt he just would never be very good at it. But, being a journalist, he decided to turn this shortcoming into investigation.

Lo and behold, he eventually became the 2006 USA Memory Champion by memorising a deck of 52 playing cards in just 1 minute and 40 seconds, setting a record in the process. This then was chronicled in his best-selling book Moonwalking with Einstein, the title being a nod to the memory palace technique he learned in his experiment.

The only reason Joshua Foer became a best-selling author and a memory champion is precisely because of how poor he felt his memory was.

Mediocrity is, and can be, when channeled properly, an intensely powerful fuel towards success.

What’s your mediocre?

If Joshua could become a champion of memory, people can go from frightened to death to world champions of public speaking, what’s your mediocre? What is that one skill you are so painfully bad at, and you are so uncomfortable being bad at, that you could actually turn around and transform into your greatest strength?

Many people have done it before you. The door is wide open, you just need to embrace mediocrity, and tune into your Failure Fuel to achieve transformational growth.